- Home

- Flack, Sophie

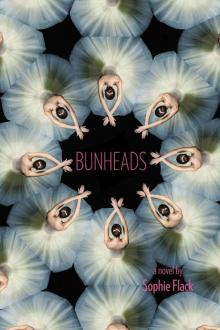

Bunheads Page 9

Bunheads Read online

Page 9

We lunge away from each other and then piqué back together again.

“You know that Emma understudied the duet last year,” she whispers, “but she’s still out, and Leah’s gained so much weight that I doubt they’d ask her to learn it.”

Since Temperaments is coming up in a few weeks, we’ll start rehearsing it soon. We switch our weight, then piqué into an attitude and pose in B-plus.

“I mean, I would so much rather do classical than Jason’s weird modern stuff,” Zoe says, posing with her arms jutting forward.

“Oh, loosen up,” I whisper. On the count of six, we kneel with our heads down, and Zoe and I are practically touching. (Conveniently, this makes it easier to talk.)

“Listen to you,” she says. “Ms. Goody Two-shoes, you’re one to talk. Unless that musician of yours is becoming a bad influence?” We stand and thrust our hips forward and then shift our weight again.

“Hardly,” I snort. “Considering I haven’t seen him since, like, November.”

“Are you thinking about Matt, then?”

“No!”

“Well, you should keep your options open,” Zoe says. “I’m sure Jacob’s keeping his open, if you know what I mean.”

I shoot Otto a look, but his attention is on Mai, whose pale skin now glistens with sweat. “What?” I ask Zoe.

“If he’s as cute as you say he is, there must be another girl out there.”

It’s not as if I haven’t wondered about other girls before, but hearing Zoe say it makes me feel terrible. “Oh yeah? Thanks for the vote of confidence.”

“All right!” Otto calls, his voice echoing in the empty theater.

Zoe and I freeze, ready to be reprimanded for chatting. But instead Otto is simply offering that half smile of his—the most we ever see—and motioning us off the stage.

“Okay, thank you,” he says. He touches Mai’s arm protectively. “Save a little for tonight.”

Back in our dressing room, Leni is doing some insane yoga pose in the corner. She’s balanced on her hands, with her feet tucked behind her neck.

“God, how do you do that?” Zoe mutters, flinging herself into her chair. “You look like a pretzel.”

“It opens up the hips,” Leni says calmly.

I collapse onto the floor and then sit up so I can stretch my hip flexors. I tell myself to stop worrying about Jacob, to focus on the upcoming performance and the rehearsals tomorrow and the next day. But then I call him anyway, and this time I reach him.

14

It’s bitterly cold, and the sidewalks have hillocks of old ice. As I walk to meet Jacob, the wind whips around the buildings so fiercely it seems to get under my clothes. I blow my nose, and I swear I can feel it getting bright red and swollen. (All of us in the dressing room have colds now; the debris on the floor includes tissues and nasal-spray bottles and cough drop wrappers, in addition to the normal piles of clothing and corn pads.)

Jacob said he’d be waiting on the steps outside the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and I find him leaning against the massive face of the building, thumbing through a book. He’s bundled up in a navy blue peacoat and a scarf that looks like something my grandma might have made. My heart does a tiny leap in my chest, then settles. He leans in and kisses me on the cheek.

“Long time, no see,” he says with a grin.

I smile up at him. “So how was your trip?”

Jacob chuckles as we turn to walk inside. “If I never see another bottle of rum in my life, I’ll be happy. And I’d like to never hear another karaoke version of ‘Cheeseburger in Paradise.’ ”

I nod understandingly. My dad plays Jimmy Buffett once in a while, and his music always makes me want to bury my head under a pillow. “I promise not to burst out in song,” I say. But I hum a few bars anyway, and Jacob ducks away, covering his ears.

“Please stop,” he moans, and I can’t help but laugh.

Inside, the great hall is thronged with people. The sound of their collective voices echoes in the marble space, a murmur amplified into a wordless roar.

“I love the Met,” I sigh.

“Me too,” Jacob says. “It’s one of my favorite places in Manhattan.”

“I came here in August,” I say. “Before fall season. I stood for, like, an hour in front of Madame X. You know, that John Singer Sargent painting?”

Jacob nods. “I do. I love Sargent.”

“I read that Madame X—I don’t remember her real name—was so spoiled that she almost couldn’t even stay still for her portrait. Sargent called her a woman of ‘unpaintable beauty and hopeless laziness.’ ”

Jacob laughs. “Laziness! You wouldn’t know a thing about that, would you?”

I shrug. “Hey, I sleep in on Mondays. Like today—I got up at nine thirty!”

“If that’s your definition of laziness, the world could use more lazy people like you.”

I put my hand in the crook of Jacob’s elbow as we wait in line to pay admission. “So where do you want to go?” I ask him. “I bet you’re the modern-art type.”

“I like my Picassos and my Duchamps,” Jacob says, handing the cashier a twenty. “But I have another place to take you first.”

“I hope it’s not Arms and Armor or the American furniture wing,” I say. He hands me a little purple button, which I affix to my coat. “Because I don’t really care about axes or Tiffany side tables.” I glance at the museum map on the wall. “And I hope you’re not thinking of taking me to the Degas ballerinas, because, believe me, I’m familiar with those. Degas and his dancers are practically the only art a bunhead knows.”

“Nope. Hang on.” He pulls out his phone and sends a quick text to someone. There’s the beep of a reply, and then Jacob nods and takes my hand again. “Okay, we have to hurry.”

“Hurry where?” I ask as he pulls me toward the elevator.

But Jacob doesn’t answer; he only smiles as we enter the car. When the elevator stops, we’re on the top floor of the museum, which, compared to the crowded hall below, seems almost deserted. Our footsteps echo as we walk down a corridor lined with black-and-white photographs of exotic birds.

A guard is standing by the doorway to the roof garden. “Hey, Frank,” Jacob calls, and Frank, a young but balding guy wearing thick hipster glasses, raises his hand in a salute.

“Don’t know why you want to go out there on a day like today,” Frank says, “but whatever, dude.” Then he opens the door with a key from a ring of them and motions us through.

Jacob steps into the chilly, pale sunlight, and I follow. The roof is empty and bare, and I turn to him, wondering why he’s brought me here. If he wanted fresh air, we could have just stayed on the steps outside the museum.

He reaches down for my hand as we walk to the edge and look down over Central Park. Far below us the ground is brown and strewn with rocks. The trees, with their bare gray branches, look like skeletons of their summer selves.

“Ever been up here?” he asks.

I shake my head, my teeth chattering a little.

Jacob clucks his tongue at me and pulls me closer; he opens his coat and tucks me inside it to protect me from the wind. “And you’ve lived here for five years?” he asks. “I figured you hadn’t been up when it’s closed, but never? They have exhibits when the weather’s nicer: Frank Stella, the sculptor, and Claes Oldenburg, the pop artist. There’s even a café.”

Maybe I should be embarrassed by my failure to frequent the Met and its apparently fabulous roof, but all I can think about is how warm I am standing near him. I wish I could live in the folds of his coat forever. It reminds me of the soft velvet of the wings. “I don’t have a lot of time….” I murmur.

Jacob turns and gazes out over the trees, and then he looks back at me. Our faces are so close, we could almost kiss. “You’re standing on the rooftop of the greatest museum in the world, looking out over the greatest city in the world—that’s something to make time for.” His voice is soft but earnest.

I shiver,

but whether it’s because I’m cold or because I’m close to Jacob, I can’t tell. “Are you lecturing me? If you are, you can quit, because I’m making time for it now.”

Jacob laughs. “I’m going to take all the credit for it, then,” he says. “Since it was my idea to meet here.” With his arm still around me, he leads me around the rooftop. “I like it up here because in the winter you can see everything. In the summer the park is just a sea of impenetrable green.” His fingers tighten around my shoulder, then loosen again. “I guess it’s just a matter of perspective. Things are prettier in June, but they’re clearer in January.”

“That sounds like a metaphor for something,” I say.

He laughs again. “Yeah, it does. But for what I’m not entirely sure.” He runs his hand through his dark hair. “I also wanted to impress you with my ability to sneak you into a closed roof garden.”

“I’m impressed,” I assure him.

He points out various buildings across the park—the Majestic, the Dakota, the Langham, and the San Remo, all on Central Park West. I half expect an architecture lesson (certainly, I’d get one if my dad were here), but thankfully Jacob doesn’t say anything about neo-Italian Renaissance facades or art deco motifs.

“You know, John Lennon was shot right outside the Dakota,” he says, pointing across the park.

I have my own trivia about the Dakota, which I know because of a documentary I got for Christmas/Hanukkah one year. “And Rudolf Nureyev lived in the Dakota,” I say. I think about watching him leap across my TV screen. I wish I could have seen him dance live, but I was only a toddler when he died. “He was one of the greatest dancers who ever lived.”

We’re quiet for a minute. I look up to see Jacob’s blue eyes searching my face. “This may seem like a weird thing to ask, but I’ve been wondering… what’s it like to dedicate your entire life to one single thing? You’ve got to be so devoted.”

I shrug. “The only way to really succeed is to give yourself completely to it. It’s kind of like the Olympics, but it’s every day of our lives.”

“That singularity of purpose.” He thinks for a moment. “You’re like Captain Ahab in Moby-Dick, but without the whole psychotic, evil thing.”

“Wow, thanks,” I say. And I make a mental note to add it to my reading list.

“His one goal—to kill the white whale—drives him mad and ultimately kills him and almost the entire crew,” Jacob explains.

“Oh, great. That sounds like just the kind of person I want to be.”

He laughs and pulls me closer to him.

“But you know I do more than just dance,” I say. “I mean, I…”

But then I’m at a loss. What else do I do regularly? I can’t think of anything besides write in my journal. I pick up a stray dead leaf from the ledge and rip it into shreds. “Never mind. Maybe I am Ahab.”

Jacob rubs his hand across my back in little circular patterns. After a few moments he turns to me, smiling. “I think you’re probably a lot more attractive than Ahab.”

I laugh and punch him in the arm. Lightly, but not too lightly.

“Are you hungry?” he asks, smiling.

“Starving,” I tell him.

I tuck my arm through his again as we take the elevator down and pass through the halls filled with Old Master paintings. I point out a Goya I like; Jacob says he loves El Greco.

As we make our way to the lobby, he says thoughtfully, “Don’t take this the wrong way, but the ballet world seems almost cultish.”

I turn to him. “What do you mean?”

Jacob smiles uncertainly. “I mean, think about it….” he says.

“What? Just because we’re expected to behave a certain way, and we follow strict schedules and rules? I mean, we’re just disciplined.” I stare at my shoes as I stride toward the door. But then I stop and look up. “But then again, Otto does kind of reign over us. Like, his word pretty much determines the course of our lives. And we can never question him—I hardly know anyone who’s even talked to him. So maybe you have a point.”

“I didn’t mean it in a bad way,” Jacob says.

“Oh, you meant it in a good way?” I laugh. “Because cults have such a great reputation. Well, whatever. If we’re a cult, we’re a very artistic and high-minded cult.”

Jacob laughs, too. “You’re an amazing cult,” he says, leading me down the Met steps.

We walk east to Lexington Avenue to catch the number 6 train downtown. The subway car is crowded, and we get separated in the crush of people. I’m wedged between a stroller and an overstuffed backpack, while Jacob is opposite me, pressed up against the door. For a minute, I wish he were more like Matt, who would never take anything but a cab—or maybe a limo. But then Jacob smiles at me from across the car, and a wave of excitement washes over me. As the train screeches along the tracks, taking us to the East Village, I feel as though Otto and the Manhattan Ballet are miles away. I feel free and light—if a little squashed.

We get out at Bleecker Street and walk to a cozy Italian restaurant on Second Street.

“This place is one of my favorites,” Jacob says. “Il Posto Accanto. The name means ‘the next place.’ ”

The room is small and dimly lit by flickering candles. A huge bouquet of flowers sits on a bar next to colorful platters of antipasti. Against the far wall, a long mirror reflects us back to ourselves, and I notice that my nose is red from the cold.

“So, I played at Gene’s again last week,” he says as he pulls out my chair.

“Did you sing about waffles?” I ask teasingly.

He fakes a look of indignation. “As a matter of fact, I have a new song cycle that has nothing to do with breakfast. It’s all about…” and here he pauses, as if trying to decide whether to tell me. “It’s all about dreams, actually. It sounds kind of corny, but it’s not, I promise.” Then he looks at me hopefully, expectantly, as if my opinion matters. It’s not a look I’m used to.

“I think it sounds great,” I tell him. “I can’t wait to hear them.” Thankfully, he says nothing about the Pete’s Candy Store show that I missed, or the fact that he has sent me invitations to a dozen other shows I’ve failed to go see.

A pretty waitress with a tattoo of a snake on her wrist comes over to give us our menus, and I scan my options. Zoe had instructed me on the proper date ordering technique. “Pick the thing that won’t make you look like you were raised by wolves,” she’d said. “For instance, forget spaghetti.” It seemed like good advice at the time, but I realize that with Jacob, I don’t really have to worry. I bravely order salmon fettuccini.

Jacob asks for the porcini risotto and then turns to me. “And actually I wrote a song for you, too,” he says.

Immediately I can feel myself flushing, and I look down. I’ve always wanted someone to write a song for me. (Find me a girl who hasn’t!) “Really?” I almost whisper. There’s a part of me that doesn’t believe he means it. “What’s it called?”

And now it’s Jacob’s turn to blush. “ ‘Girl in a Tutu,’ ” he says. He looks out the window and twists his hands together nervously.

I’m dying to hear the song. I want to reach across the table and hold his hand, but I’m overcome with shyness. Eventually I find my voice. “I love it,” I tell him.

He turns to look at me. “But you haven’t heard it yet,” he says, smiling.

“Well, of course I want to.” My throat feels dry, so I take a sip of wine. “But so far, so good.”

“I’m glad you approve,” Jacob says.

“You could sing a little of it for me now,” I say. Because I really have to know: What does it say about me?

“Only if you dance a little for me now,” he responds, grinning.

I shake my head vehemently. “Never. Only if you’re in the Avery Center audience.” I say this because, for one thing, ballet—unlike singing—is not something one can quietly do at one’s dinner table. And for another thing, I prefer it when my audience is invisible.

&n

bsp; “Only if you’re in a tutu, you mean?” Jacob asks.

I smile. “Something like that.”

His attention is momentarily diverted by the delivery of a plate of spaghetti to our neighbors. “Did I tell you about Paulo?” Jacob asks suddenly. “The spaghetti reminded me.”

I shake my head.

And then Jacob begins to tell me more about the after-school program he works at in Spanish Harlem, and about a boy named Paulo who follows him around like a puppy. Paulo is always getting into trouble for one thing or another, and he seems to take great pleasure in being a source of chaos. “Once,” Jacob says, “he took a piece of spaghetti he’d saved from lunch, and stuffed the entire thing up his nose.”

“Ew!” I say.

Jacob holds up his hand. “Wait—it gets better. Somehow he had the one end coming out of his nose, and he got the other end coming out of his mouth, and he basically flossed the back of his throat with the noodle.”

Hearing this, I let out a little snort of laughter. Embarrassed, I look around as if trying to spot the person who made that sound.

“What was that?” Jacob smiles. “I didn’t take you for the snorting type.” And then he reaches over to tickle me.

“I have no idea what you’re talking about,” I say indignantly. “It was that guy behind me!” Pretty soon I’m desperately trying to stifle my giggles and wriggling away, trying to dodge his hands. Eventually he gives up, and I catch my breath and relax in my chair. Our eyes meet. Suddenly he reaches across the table, takes my face in his hands, and leans toward me.

Oh my God, he’s going to kiss me, I think. I feel a physical, almost magnetic pull toward him; I close my eyes. There is one delicious millisecond of anticipation, and then our lips touch. I feel the surprising softness of his mouth. A surge of energy rushes through my body, and I’m hot and cold at the same time. It’s as if I have a fever, but the feeling is one of indescribable sweetness.

After a moment Jacob pulls away and sits back, his blue eyes glowing.

I want him to kiss me more, but now the waitress is beside our table. Her face betrays no reaction to our PDA. I suppose she’s seen a lot worse in her day.

Bunheads

Bunheads