- Home

- Flack, Sophie

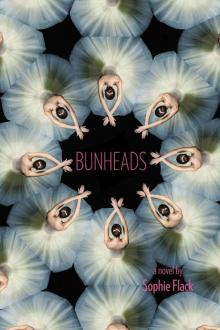

Bunheads Page 6

Bunheads Read online

Page 6

I want to feel calm, but my heart flutters lightly and quickly in my chest. I’m not nervous, I tell myself; I’m just excited.

I relish the moment before the curtain rises, when the audience is waiting. In that moment, time seems to slow down, and it’s as if the whole world is hushed. I stand alone in the wing and feel the soft velvet of the curtain against my skin. I imagine the conductor raising his baton on the other side, and as his arms come down, the bassoons begin to play, followed by the strings.

I wave at Sam from across the stage, and on my count, I dash out into the light. We meet at center stage, and he grabs me by the waist as we begin the pas de deux. I imagine that beams of light are coming out of my fingertips and my toes. I can’t see Bea and Daisy and Zoe, but I know they are watching intently from the wings: Bea looking thrilled, Daisy half-awed and half-jealous, and Zoe sour, as if she just ate a lemon. And I’m pretty sure Otto and Annabelle are somewhere in the audience, too, watching intently. But I put that out of my mind and dance just for myself, as if Sam and I are alone in an empty theater.

There are moments onstage when everything else falls away, and I think of these as the magic times. In the magic times, I feel completely in control of my body; my limbs do everything that is asked of them, and I feel as if gravity has no hold on me. Tonight, dancing Lottie’s part feels just like that.

During Sam’s solo, I catch my breath in the wing before I reenter. I adjust my costume and try to slow my breath. I’m intensely focused on the performance, and I wait for my entrance like a cat with ears perked.

Then I run onstage to meet Sam for the finale. As I do the final turn sequence and run and leap into the wings, I nearly land on Harry, who’s tucked in behind the curtain.

“I got you!” He laughs and grabs me so I don’t fall.

“Sorry!” I say breathlessly. “Didn’t see you there.” My chest is heaving from the exertion, and my legs feel like jelly.

“Naw, it was my fault, hiding out here to watch you,” he says, dropping his hands now that I’m stable. “You were magnificent.”

By now Harry is usually up in the flies, which is the towering system of ropes, counterweights, pulleys, and scaffolding that allows the stagehands to part curtains, move lights, and rotate set pieces onstage. I wonder if he came down to the stage level to watch me. He normally doesn’t even do that for the principals, so this would be a rare compliment. “Really? You think I was okay?” I ask.

He nods. “Absolutely.”

My face flushes with pleasure. Unlike anyone else I can think of, Harry has no ulterior motive for praising me. And since he’s been watching ballet for twenty-some years, he can be an exceptionally harsh critic. “Now get out there and take your bow,” he says, and gives me a playful shove.

Then Matilda pokes her head out from behind one of Harry’s massive legs. “You were beautiful,” she gasps.

“Thanks!” I say. I reach out to ruffle her hair, and then I run onstage to receive my applause.

I’m back in the dressing room, peeling off my sweat-soaked tights, when Bea comes racing in with a copy of the New York Times. She’s still in her stage makeup, and her face is dewy with sweat. “Han, look!” she says, jabbing her finger at the paper. “I stole this from the Green Room—the review mentions you!”

I rush over and snatch the newspaper from her. “Gimme,” I say, “please.” I begin reading, my heart in my throat. I skim past the mentions of the principals and soloists, of the ballets I wasn’t in, searching for my name. And then I find it, in the fourth paragraph:

Hannah Ward, a late-season fill-in for Lottie Harlow, has marvelous focus in Division at Dusk, Otto Klein’s latest ballet. She dances with a pleasing mixture of innocence and impulsiveness, and her energy is contagious. While her phrasing is calculated, her dancing seems spontaneous and youthful; her legs and feet are brilliantly precise.

I look up with tears in my eyes. I can’t believe those words are about me. Quickly I read the sentences again.

Bea is beaming at me. “Isn’t it amazing?” she whispers.

“What?” says Leni. She comes in from the bathroom with a towel wrapped around her head. Leni has long, sandy-blond hair and wide blue eyes; she looks a little like Brigitte Bardot, but her voice is low and mannish, with a thick German accent.

Bea turns to her and chirps, “Hannah got a write-up in the Times, and it’s totally incredible.”

Leni shifts her gaze to me as she dries her hair. “Wow, that’s great, Hannah,” she says. She bends over, rubs the towel vigorously over her head, and then stands up again. “Maybe now you’ll be moving up in the world, little Balletttänzerin.”

In my mind, I see Otto nodding in approval when I finish my performances; I see my name featured prominently on casting lists; I imagine learning solo roles and practicing them on a silent, empty stage. I imagine Otto telling me that I’ve been promoted. How I’d scream and cry and call my mom, and then she’d start crying, too.

Zoe and Daisy come in from their ballet. Daisy nearly trips over the old carpet that curls up at the edges of the room. “Ow!” she yells. “Do they want me to break an ankle or something?” Then she turns to me. “I heard about your write-up,” she says. “That’s so great! Maybe I should add you to my autograph collection.”

“Very funny,” I say. Daisy’s been collecting the autographs of famous dancers since she was six years old. It was her mother’s idea; it was supposed to motivate Daisy in her own dancing.

Sarcasm aside, I think Daisy’s probably happy for me. And she’s certainly being nicer than Zoe, who says nothing at all. She’s been in a terrible mood ever since I got thrown on. She can’t believe she missed out on an opportunity purely by chance; had she been in the wings, she could have danced Lottie’s part instead.

If I were Zoe, I’d be jealous, too.

“And I bet this leads to other parts,” Bea says confidently as she scrubs off her makeup.

At this, Zoe turns around so quickly she almost knocks over a chair. She storms out the door.

I look at Zoe’s empty seat, and for a moment I indulge in the guilty feeling of triumph. The fact that she feels so threatened is a sign that my star is ascending. We’ve been neck and neck for years. And yes, it was sheer luck that I was in the wings, instead of Zoe—but it wasn’t luck that I danced well and got written up in the Times.

Beside me Bea finishes removing her stage makeup and throws on her coat; Daisy crams a hat over her bun and waves.

“See you later,” they call, and head out into the chilly November night.

Alone in the room, I look at myself in the mirror. My blond hair is in a messy ponytail. My cheeks are still pink from my performance, and my legs are aching. I stand up and inspect my body. So the Times reviewer thinks I was “brilliantly precise,” which is amazing. But was Helga right? Am I just a little bit softer than I used to be?

With my hair pulled tightly away from my face, I look lean and determined. But is it enough? Will they ever tell me it’s enough?

9

As I walk down the hallway after rehearsal, a little girl in a pale pink leotard runs by. She stops in front of the vending machine and stands on her tippy-toes to reach for the coin slot.

Thanks to The Nutcracker, which we’ve just begun to perform, the backstage hallways are filled with eight-and nine-year-old dancers. They stare at us and mimic our stretching; they bug us for signed pointe shoes and autographs. They think we’re the greatest, which can be cute or annoying, depending on your mood.

The ballets we dance in our regular repertory seasons are contemporary and generally plotless, and we rotate through them as the weeks pass. But when Thanksgiving comes (which Bea and I celebrated this year with Korean takeout and a Mad Men marathon), it’s time to perform The Nutcracker. Once Nutcracker starts, we dance the same parts and listen to the same score night after night, for fifty consecutive performances, until New Year’s Eve. It’s kind of like eating SPAM after a plate of filet mignon.

“Do you need a hand?” I ask the girl.

She freezes, and her eyes go wide. I can practically hear what she’s thinking: Oh my God, it’s a real ballerina! The little girl nods slowly, too awed, apparently, to smile.

I pick her up by the waist and align her with the coin slot. She slips her quarters in, and a few seconds later a Diet Sprite clunks down.

“Is that what you wanted?” I ask. I think she must have pressed the wrong button. She’s a kid—she should have Fanta or something.

“Oh yes,” she says. “Diet Coke’s my favorite, but the machine never has that.” She retrieves the soda and grasps it tightly in her little hands. “Thank you,” she says, and offers me a little curtsy.

“No problem,” I mutter.

I pick up the phone and dial Jacob’s number. “They’ve got eight-year-olds on diets,” I say when he picks up the phone. “They’re, like, total baby bunheads.”

“Huh?” he says. His voice sounds low and sleepy.

“Were you napping?”

He clears his throat. “Who, me? What? No.”

I can tell he’s lying, but I decide not to tease him about it. “Well, I just called to tell you that I kind of hate The Nutcracker,” I say.

He laughs. “Wait, I thought everyone loved The Nutcracker.”

I groan. “Yeah, maybe if you’re sitting in the audience, and you’re, like, ten years old.” I grip the phone as I stride down the hall to the dressing room. “After about the fifteenth performance, it begins to feel completely soulless. We do it every season, so you’d think people would be bored of it by now. But we sell out every single show. And tickets are, like, eighty bucks.”

“Sounds rough,” Jacob says. I can hear him running water and then taking a sip. “But I bet you look nice in your Sugarplum costume.”

“If only,” I say. “Sugarplum is a principal role. I’m a lowly Flower and a Snowflake.”

“Well, I’m sure you make a gorgeous Snowflake. But what does this have to do with eight-year-olds on diets?” he asks.

I push open the dressing room door and flop down onto my chair. “Oh, I don’t know. One of the kids in the show—there are all these parts for little kids—had me get her a Diet Sprite just now. I mean, it’s one thing if you’re hired to be a graceful waif, but a little girl? That’s sick.”

“Better a Diet Coke than the sixty-four-ounce Slurpees my kids in the after-school program show up with,” Jacob says. “They’re rotting their teeth out of their heads.”

“Oh yeah, I guess you have a point,” I admit. I look at the clock. “Crap, I should go. I’ve got rehearsal.”

“Wait. So there’s this band playing at Rockwood Music Hall this Saturday, and some of my buddies and I are going,” he says.

“Oh, cool.”

“Yeah, so what do you say? I think Bea might really dig my friend Drew.”

“I won’t be done with the performance until eleven.”

“Oh. Okay. So, all right, I’ve got my calendar right here. I’m free most nights after eleven, and I’ve got all my Mondays open. What do you say? How about dinner at Café Mozart? Or there’s this great Indian place on Fifty-Eighth between Seventh and Eighth….”

I want to see Jacob again, I do. But I think back to the experience of dancing Division at Dusk, and I also know that I want more parts like that. They won’t come without extraordinary effort. If this is my year, I have to keep pushing myself every single day; besides rehearsals and performances, I need to take Pilates and yoga classes. Already Otto must be contemplating casting the winter season, and I want him to think of me. So I can’t risk being distracted.

Focus, I tell myself. Focus.

I picture Jacob’s face, the line of his jaw and the faint shadow of stubble on his cheek. I close my eyes. “You know, I just can’t right now,” I say. “I’m sorry.”

There’s a long, tense silence. I can hear Jacob breathing on the other end of the line. Pretty soon I can’t stand it. “I’m really, really busy.” I feel helpless, but it’s true.

Jacob clears his throat. “Wow, I don’t know too many nineteen-year-olds who can’t make time to hang with friends. You sure are different, Ward.” He pauses. “And I like that about you. And I think what you’re doing is great. I just wonder if it leaves you any time for a life.”

I bristle at this. “Dancing is my life,” I say without thinking.

“Well, then—” Jacob starts to say.

I interrupt him. “But I want to see you.”

“Well, call me when you’ve got a free moment,” Jacob says. “Okay? I’ll probably be here.”

When I hang up the phone, I have a queasy feeling in my stomach. Probably?

10

The party invitations start coming in November, and the closer it gets to Christmas, the faster and thicker they come. “Please join us for a celebratory dinner in honor of the dancers of the Manhattan Ballet”; “The pleasure of your company is requested at a cocktail reception hosted by Mr. and Mrs. So-and-So”; “Lights! Camera! Dance! Celebrate the season with the Whatever Foundation, proud sponsors of the Manhattan Ballet.”

The hosts are always people who give money to the ballet, and so we’re strongly encouraged—and sometimes basically forced—to go. Otto doesn’t consider patron parties a distraction. As far as he’s concerned, attending them is a part of our job. And even though they’re a little boring sometimes, they’re also pretty glamorous.

Tonight’s party is hosted by one of the ballet’s biggest patrons, which is why Bea, Daisy, Zoe, and I are on the Upper East Side in the middle of a December snowstorm.

“These heels were so not made for snow,” Zoe whines, adjusting the strap on her patent leather Louboutins.

“I told you to wear leg warmers, like I did. You just take them off in the elevator and stuff them into your bag,” Bea replies.

When the private elevator car opens onto the marble foyer of the penthouse, Bea, who is wearing her hair braided and pinned on the top of her head like Heidi of the Alps because she thinks it draws attention away from her slightly protruding ears, pokes me in the ribs. “Hey,” she says. “Is this amazing? Or is it just gauche?”

Bea is from New England, where rich people drive ancient Volvos and let the wallpaper in their wainscoted dining rooms fade and peel. People with money let old things stay old. But in New York, there’s no room for Yankee modesty. All the Manhattan Ballet’s patrons seem to live in twenty-room apartments with views of Central Park. Every piece of furniture, every painting, and every pillow is selected by interior decorators, and every mote of dust is swept up by uniformed maids.

I give my vintage velvet-collared jacket to the coat girl and smooth the front of my black floral-print dress as I take Bea’s arm. I look at the huge gilded mirror that hangs in the foyer and then up at the trompe l’oeil ceiling, which features fat little cherubs floating around in a blue sky. “I think it’s sort of gauche,” I say in a low voice.

Bea nods as she eyes the giant bouquets of snow-white lilies and roses that dot the room. “Yeah, that’s what I was sort of leaning toward.”

As we step into the parlor, a waiter dressed head to toe in black sidles over to us. “Sugarplum-tini?” he asks smoothly, holding out a tray of lavender drinks with snowflake stirrers in them.

“Oh my God, they’re purple,” Bea mumbles. I nudge her.

“No, thank you,” I say to the waiter. “I’m going to find the champagne.”

He nods deferentially. “Allow me to procure you some,” he says, and glides away.

Bea fiddles with the hem of her sequined BCBG mini. “I never know what to do at these things,” she says.

“Drink,” I say. “Eat French cheese.” I point to a table piled high with cheeses, olives, and fruit. “Or desserts,” I say, gesturing to the table of petits fours, tartlets, and delicate little cookies. Waiters circle the room with plates of delectable-looking appetizers: mini lobster rolls, stuffed figs, and tiny quiches.

&n

bsp; I walk over to the cheese table and pop a bit of chevre into my mouth. “I wonder who they think is going to eat all this stuff,” I say. “Not the ballet dancers. Zoe’s vegan, Daisy’s back on her fruit diet, Adriana is doing her raw-food thing, and Lottie hasn’t had carbs in thirty years.”

“The boys will eat it.” Bea points across the room. “Look at Jonathan. It looks like he’s trying to murder that salami.”

I giggle, and Jonathan, who’s wearing a fitted gray suit and a navy bow tie and is sawing into a salami like a starving man, looks up and waves his knife at us. “Hi, ladies,” he calls. “You know I love me a charcuterie table. And if you see the cute guy with the shrimp skewers, send him my way.”

I look down and see hot-pink socks peeking out from his shoes.

The waiter returns with our champagne, and then Daisy comes bouncing over in a polka-dot dress that she probably bought in the children’s section at Macy’s. “Oh, hey, you guys,” she says. “Did you see Julie as the Sugarplum? She totally blew my mind tonight.”

“Yeah, she was great,” I say. Julie is a principal dancer, and she’s tall and strong and has eyes so dark they’re almost black. But the truth is I didn’t watch her; I was busy composing witty texts to Jacob and then deleting them before sending them.

The waiter returns with a glass of ginger ale for Daisy, since she’s so obviously underage. “Can’t,” she says, beaming at him. “The calories!” Then she turns to me. “Did you hear that Emma pulled her calf? She’s going to be out for a while.”

“I heard,” I say grimly. “She was my alternate, remember?”

“Oh, right—I forgot you were supposed to have nights off.”

Bunheads

Bunheads