- Home

- Flack, Sophie

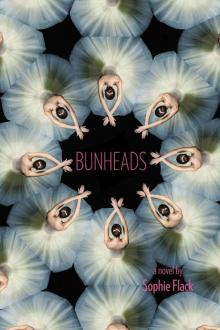

Bunheads Page 4

Bunheads Read online

Page 4

By the door, Lottie Harlow twists her auburn hair up with a mouthful of long pins. Her oatmeal-colored sweater falls from her bony shoulders. The boys, who don’t have to worry about their hairstyles, roll their calves out on tennis balls and do push-ups.

We start out by finding our places at the barre. Six barres are arranged in the center of the studio, plus the ones lining the walls. I squeeze in between Bea and Jonathan, who lives in my building and looks kind of like Bradley Cooper. He blows me a kiss and nudges his bag over with a pointed toe. If he liked girls, which he doesn’t, I would have developed a crush on him long ago.

When Mr. Edmunds, the ballet master, enters, he motions to the pianist, who plays a slow, simple melody. We begin with a series of deep knee bends that engages our whole bodies. (You can always hear the pop and crack of people’s hips and knees during pliés.)

Then, as Mr. Edmunds demonstrates the grand battement combination, I tap Bea’s hand and she moves closer. “I met someone,” I whisper. “His name is Jacob Cohen. He’s a musician and he’s really cute.”

Bea’s blue eyes open comically wide and she gets a big grin on her face, but then she has to get into position for the combination. After a moment she leans back over the barre. “No way! When was this?”

“Last night.” I smile, feeling mischievous.

“You actually went out?” she whispers. “But you’re such a goody-goody!”

“You should talk,” I reply with a giggle. “But I know—it’s totally unlike me.” And I feel guilty because I have a packed schedule today, I think. I just hope I don’t pay for it in tonight’s show.

Then Mr. Edmunds passes by us, and we both stare straight ahead. He walks around the room, frowning or nodding, depending on the technique of the dancer he’s watching. His salt-and-pepper hair is feathered: It’s a little too pouffed on top, and a little too long at the back. He was a principal dancer with the Manhattan Ballet twenty years ago, and he loves to poke us in the stomach or the bum to encourage us to tighten up. When he does this, we usually make puking faces behind his back.

“Oh, I wish you would have taken me,” Bea moans. “I can’t believe you met a real, live nondancer.”

“Me either!”

In the second half of class, we move to the center, where we work without a barre. The floor is sprung and layered with linoleum, almost identical to the stage. Mr. Edmunds demonstrates another combination—something slow, an adagio—and we follow his lead. I try to talk to Bea again during petit allégro, but I swear Mr. Edmunds is keeping an especially close eye on us today.

So—silently—we balancé, we pirouette, we leap. My heart beats rapidly in my chest, and my leg muscles burn. The tempo of the music increases, and we begin to exaggerate our movements until we are jumping across the floor in grand allégro. Pretty soon my face flushes, and my breath comes in gasps. At this point I’m breathing so hard I wouldn’t be able to talk to Bea even if I had the chance.

After class I take a quick sip of water and then head back to the studio, where Otto is working with sinewy Lottie, choreographing his new ballet. Under the fluorescent lights of the studio, Otto’s dark, deep-set eyes glitter. His dark hair has just a dusting of gray around the temples, and his olive complexion stands out against Lottie’s porcelain skin as he clutches her tiny wrist to demonstrate a promenade. Even though he walks with a limp from a botched hip replacement, he’s still considered the best partner around and regularly demonstrates choreography. If you saw Otto on the street, you’d think he was handsome but completely unapproachable.

Which he basically is.

“And développé,” Otto tells Lottie.

As understudies, Zoe and I mirror her steps along the barre in the background. Otto has been changing the choreography as he goes, so one day he asks for piqué turns and the next day he wants grands jetés. It’s hard to remember which version is which.

When we first started rehearsing, Zoe always tried to stand in front of me, but once she figured out Otto wasn’t actually going to rehearse a second cast, she turned the level of competition down a notch.

“Of course we’re understudying the one dancer in the company who, like, never goes out,” she whispers as she marks the piqué turns.

“I know,” I say. “She’s, like, strong as an ox.”

“And yet skinny as a carrot stick.”

I stifle a giggle as Zoe leans in close to me. “I wish she’d eat a bad mussel or something,” she says.

“But she hardly eats,” I remind her. “Or so they say.”

“Well then, we should spike her water with laxatives,” Zoe says, leaning against the barre and grinning naughtily.

I sigh. “I’m so bored. Haven’t we done this section fifty times already? Maybe I should pretend I have menstrual cramps just to get out of here.”

“Oh my God, girl problems! Otto would be so uncomfortable that he’d just shoo you out of the room,” she whispers with a giggle.

“It’s worth a try,” I say, but Zoe shakes her shiny blond head at me.

“This is just part of the job,” she says.

“I know, I know. The crappy part,” I mutter.

So I keep marking the steps and try not to think about the futility of my hopes to dance Lottie’s part. As Otto moves on to the adagio section, I allow my mind to wander a little. I imagine what it would be like to kiss Jacob, the cutest singer-songwriter in all of Manhattan. Considering I pretty much melted from a single peck on the cheek, I’m worried that a real kiss would turn me into a quivering puddle of goo. But I’m willing to take the chance.

Of course, who knows when I’ll get that chance again? Between rehearsals and the nightly performances, my schedule is beyond packed. After this rehearsal, I have one for Vous and another for Prelude, then a triple-header tonight. I’ll be lucky to make it through without collapsing from exhaustion.

I sigh and look up at the vaulted ceiling. The fluorescent lights somehow create a disorienting effect, and after hours of rehearsal I always begin to feel a little dizzy. But as Bea once pointed out, the dizziness could also come from oxygen deprivation due to the lack of windows.

Suddenly Otto is standing in front of me, his dark eyes cool and appraising. “You’d better be picking this up, Ward.” He looks down his nose at me, and I feel very small.

I nod my head vigorously and glance over to see Zoe snickering in the corner. All thoughts of Jacob are banished for the next two hours.

Back in the dressing room, Daisy comes from the showers, drops her towel, and sticks out her taut brown stomach. Her wet black hair hangs almost to her waist. “I am a hippo.”

“Oh Jesus,” I mutter to Bea. I’m trying to find spare change for a soda. “She’d better not get a stress fracture from all that ridiculous dieting.”

“No kidding,” Bea whispers.

The apprentices and first-year corps girls are always getting injured because they don’t know how to pace themselves in rehearsals and they diet like crazy. When they go out, we older girls end up dancing their crappy apprentice parts.

“You know she hasn’t had a slice of bread for six weeks?” Bea whispers as she twists her hair into some new configuration. Unlike me—I pretty much always sport a basic bun or chignon—Bea likes to experiment with intricate twists and braids.

“Doesn’t surprise me,” I say.

“I don’t get it,” Daisy half whines as she flops down onto her chair. “I haven’t eaten anything but cabbage and grapefruit for, like, nine days.”

“We’re doomed,” I whisper to Bea, who rolls her eyes.

“I heard that gives you really bad…” Zoe snickers. She inspects her long, thin legs.

I try to stifle my laughter; Bea snorts.

“Oh my God, did you rip one last night during third movement?” I ask.

Daisy’s cheeks turn bright red. “Shut up. Shut up! I can’t help it!” She tries not to laugh, but she can’t stop. “It’s not like the audience heard anything. And anyway, not

everyone is born looking like Zoe.”

The mood in the room subtly changes. Bea fidgets in her seat. I find two quarters inside my makeup bag and keep pawing around for more. Zoe stands up and shifts her weight uncomfortably.

“Smoke time,” she says. She pulls a Stella McCartney jacket over her leotard, then gets up and leaves, letting the door slam behind her.

“That ain’t natural,” I whisper to Bea. “Born like that? Please. And that whole vegan trip of hers? It’s not because she cares about animal welfare! It’s all about the calories. She’d dress head to toe in leather if Vogue told her to.”

Bea nods. “And the smoking?” she says. “So gross.” She wrinkles her freckled nose.

“I know! Talk about crazy dieting—I haven’t seen her eat anything but carrot sticks in about six months. Would it kill her to eat a protein bar or something once in a while?”

Bea widens her big blue eyes. “God forbid! She doesn’t want to fill out that concave ass of hers.”

I laugh as I dig in my bag for a banana. But it’s not really funny. Daisy thinks she’s a hippo, and Zoe always complains about her big butt—and yet both of them are stick-thin. Their bodies hardly have a single curve.

I used to be like that, too: long, lean, and totally flat. I didn’t get my period until six months ago, when I was eighteen, because the intense daily exercise delayed it. But now my body is just beginning to show puberty’s effects. Surreptitiously, I eye myself in profile. I don’t have hips, but my breasts are little mounds sticking out from the rest of my body. They ruin my line. I squish them down with my hands. Much better, I think.

“Speaking of protein bars, someone’s been stealing my food,” Bea says, her perfectly arched eyebrows knitting together. “I had a whole box in here, and now there are only two left.” She stands and faces us. Her hip bones jut out of the front of her leotard. All of ours do.

“Not me,” Daisy says, toweling off her dark hair. “They’re, like, totally full of carbs.” She knows the nutrition information of pretty much any food you can name.

“Whatever,” Bea says, opening a Diet Coke.

“You really should drink water, you know,” Daisy tells her. In addition to being a compulsive dieter, Daisy is water’s number one spokesperson. She drinks about two gallons a day. “Diet Coke is terrible for you.”

“Well, so is stress-eating your way through a bag of Oreos and two packages of Doritos the way you do every time Otto looks at you funny. That really messes up your metabolism, you know.”

Daisy widens her eyes and then flounces over to the corner to sulk.

“She’s starting to get on my nerves,” Bea whispers.

“I am not dancing any of her stupid parts when she starts breaking bones,” I say.

“What?” Daisy asks from the corner.

“Oh, nothing,” I say, winking at Bea.

Then Bea quickly changes the subject. “Where is Leni? Doesn’t she have rehearsal soon?”

Leni’s the other dancer in our dressing room, but she’s seldom here because she’s more senior and doesn’t perform as much. She used to dance in the corps of the Stuttgart Ballet, and she joined the Manhattan Ballet about ten years ago. She’s thirty-four, which is pretty old for a ballet dancer. Lily used to share our dressing room, too, but she moved out a few months ago because she got pregnant. It hadn’t been planned, and Zoe had cruelly stuck condoms to her mirror as soon as she was out the door.

“Leni’s around,” I say. “I think I saw her flirting with Caleb in the hall.” I say this to tease Daisy, who has just started dating Caleb, another corps dancer. He’s eighteen, and he has brown, slightly curly hair and a thing for V-necked cashmere sweaters.

Her little face crumples—until she realizes I’m joking.

“Very funny,” she says, snapping her towel at me. “He took me to O’Neals’ the other night, you know.” She searches around in her theater case for another leotard. She’s still half naked; her tiny breasts are encased in a training bra.

“I hope you didn’t have the French onion soup,” I say. “Jonathan told me that he found a rubber band in his bowl last week.” The food at O’Neals’ is mediocre, but the location is perfect. You could throw a dinner roll out the window and it’d land right at the theater’s stage door.

Daisy wrinkles her nose. “Ew,” she says. “I had a salad, no dressing.”

“I hope you had a drink to loosen you up,” Bea says, carefully placing a corn pad on her foot.

Daisy pulls out a leotard, rejects it, and then searches for another one. Goose bumps are rising on her skinny arms. “I hate the taste of alcohol.”

“Well, good,” I say, “because you’re only old enough for Kool-Aid.”

“Like I’d drink that,” she says. “Way too much sugar.” She finally finds a clean leotard and slips it on over her tights. “Caleb ordered me a club soda.”

“Did you have a heart-to-heart about how to fix his sickled feet?” Zoe asks as she enters and flings her purse into her theater case. Having sickled feet, or poor foot turnout, breaks a dancer’s line even worse than breasts do.

“Fast cigarette,” I note.

“I changed my mind,” she says breezily.

“No, Zoe,” Daisy says, “we didn’t—because he doesn’t have sickled feet.”

“Maybe not. But I think he might dig guys,” Zoe mutters as she scoots past me.

Bea rises to Daisy’s defense. “Did your boyfriend take you on a date to the latest Manhattan Ballet board meeting?” she asks Zoe, her blue eyes flashing.

For the last month or so, Zoe has been dating Adam Kemp, whose dad is president of the ballet board. He’s kind of a jerk, but Zoe likes the proximity to power that he offers.

“Yeah, does he send you romantic texts with the meeting minutes?” I add.

Zoe runs a brush through her glossy blond hair, which reaches almost to her waist. “For your information,” she says coolly, “Adam is very romantic. So is his brother.”

“His brother? Hello?” I say. “Two at a time?”

“Oh, you are the worst!” Bea exclaims. “Someone should call your mother.”

“Considering my mother is having an affair with her grocery delivery guy,” Zoe says nonchalantly, “I hardly think she’s in a position to judge me.”

All of our mouths drop open, and then we’re shrieking for details.

When we’ve exhausted ourselves laughing over Dolly’s latest fling, we head out to rehearsal. Before I shut off the lights, I look back at the dressing room. We each have our own little counter space and chair in front of a mirror, where we sit and fix our hair or take off and put on makeup. We stick photos on the edges of our mirrors and tape posters to the cinder-block walls, and around the holidays we string Christmas lights along the wire-caged bulbs.

There are towels draped over chairs, and sweatshirts spilling out of the closet organizers that are hung on a bar at the back. The tables in front of the mirrors are littered with hair spray, lotion, deodorant, eyelash glue, and pancake makeup. It’s amazing to me that five people can make such a big mess.

Then I flip the switch—darkness.

In the hallway, Daisy turns to me and says, “Speaking of boys, what about this Jacob person Bea told me about?”

I take a gulp of water. “I don’t know when I’ll see him again,” I say. Then I link arms with Bea. “But who needs boys when I have my girls?”

And everyone—even Zoe—smiles at this.

6

One chilly October evening, a rare night off, I decide to stick around after the matinee to watch Lottie perform the part I’ve been understudying. (Jacob invited me to a show he’s playing in Bushwick, but that was just too far away for me to comprehend.) I want to see what Lottie looks like onstage, in all her costumed finery.

As I stand in the darkness of the wing, the black velvet curtain brushes softly against my skin. Onstage, corps dancers in eggplant unitards execute quick pointe work with complicated arm patterns wh

ile Lottie, in a pink chiffon knee-length dress, and her partner, tall, curly-haired Sam, are in front, moving as though the air were as thick as honey. He supports her in a sideways lift against his hip and then brings her down to face him, holding her carefully in his muscular arms. Lottie leans into him, and their lips almost touch. Then comes the moment when he lifts her in a press over his head, and she seems to float above him. But when she comes down, her face frozen in a smile, I can see that she lands wrong.

All of us watching backstage gasp as she stumbles.

“Oh my God,” I hear someone whisper.

Lottie is no longer smiling, and pain flashes in her eyes. Sam reaches out and catches her arm, trying to support her. I can see her grit her teeth, and I know just what she’s thinking: She wants to go on, but she can’t. Even though her steps aren’t even close to finished, she chassés offstage, her right foot gliding behind her as if it were part of the choreography.

Daisy skitters over to me. “What happened?” she hisses, her dark brows furrowed.

Lottie limps into the wings and bursts into tears.

“She came down wrong,” I whisper. My heart is beating double time.

Sam improvises the next section alone. At center stage he adds a set of turns that seems out of place.

Annabelle Hayes, MB’s ballet mistress, materializes out of the dark. “Hannah,” she asks calmly, “how well do you know the ballet?” Her cool gray eyes meet mine.

A wave of nausea overwhelms me. My heart starts thumping, and my breaths come fast and shallow. “I—I know it.”

I hear the words come out, and I hope they’re true. Yes, I spent those days marking Lottie’s steps, but I never actually rehearsed them. I never practiced the partnering, and I have only a basic idea of the counts.

But it doesn’t matter what my answer is. Annabelle grips my arm and pulls me to where Lottie is weeping.

Bunheads

Bunheads