- Home

- Flack, Sophie

Bunheads Page 12

Bunheads Read online

Page 12

“Where did you come from?” I ask dully.

“I fell asleep doing my spinal series on the floor. They’re so relaxing.” Her cheek has the imprint of her rubber mat on it.

I put my head in my hands.

“What?” she asks.

“Casting,” I say dully.

She sighs. “Right.”

“It all just feels utterly pointless. Why do we work so hard to get strong, to improve, if no one cares or notices?” I even lost weight, I think, just as Annabelle wanted!

Leni comes over to put her hand on my shoulder. She rubs the hard, tight muscles there for a while before she speaks. “I know it’s tough, I know. But you have to enjoy the moment. You must embrace the process of dance. How do you think I kept with this for fifteen years?”

The process of dance. She sounds like my hippie-dippie mother, with her whole “journey of creativity” trip. I push my fists into my eyeballs because I think it might help me not cry. “I thought that I loved all of it—the grueling rehearsals, the intensity, and the long hours and everything. But if I’m still doing the same parts that I did as an apprentice…” I trail off. I can feel my eyes fill with tears despite the knuckles I’ve wedged into them.

“I know how it feels. I did the Garland Dance in Sleeping Beauty for five years,” Leni says.

I look up at her. “Are you serious?”

She nods as she digs her thumb into a sore spot near my neck. “And I did Snow and Flowers in The Nutcracker for eight.”

“You’re a better person than I am,” I say.

She pats my shoulder and moves back toward her mat. “I don’t know what else I would do if I didn’t dance.”

“I don’t either,” I cry, “but there are other possibilities out there! I mean, this theater is not the entire world, contrary to what most people around here seem to think. There are museums and restaurants… and rock shows, or so I hear.”

Leni sits down, stretches her legs out in front of her, and reaches down to cup the balls of her feet in her hands. “The point is to love dancing. And once you stop loving it, it’s time to do something else. It’s just too hard otherwise.”

“I love being onstage. But it’s so painful feeling invisible,” I tell her.

“I see you, Balletttänzerin,” she says softly. “You are not invisible.”

But I must be—how else can I explain the way I was overlooked?

20

“It’s just too much,” Zoe says, twisting her pale gold hair around her fingers. She’s barefoot, wearing pink cutoff tights and a soft blue T-shirt, and she’s sitting in my chair with her feet up against my mirror, talking to Daisy, who looks both awed and jealous. “After the pas de deux, my calves feel like they are going to rip. Then I go straight into the solo with no break. I mean, the solo itself is nearly impossible. It’s like Otto’s testing me or something.”

Daisy shoves a handful of Doritos into her mouth. The tips of her fingers are bright orange. Since the last casting was posted, Daisy’s consumption of junk food has been in overdrive.

“Do you mind?” I say.

Zoe looks up and lethargically removes her feet one by one, then returns to her spot on the other side of the dressing room. She goes on, undeterred by her displacement. “I mean, it’s all jumps for what feels like forever. You go pas de chat, then grand jeté, pas de chat, then you open out into high kicks, then these chaîné turns, then all these coupé-jeté things….”

“Blah-blah-blah,” I mouth, and Daisy stifles a giggle. Zoe is oblivious; she goes on blabbing. She reminds me of my junior high history teacher, Mr. Schmidt. He never noticed that no one, and I mean no one, was listening to him.

I take out my notebook and start doodling in the margins. At least Mr. Schmidt had facts to impart—Zoe is just bragging but disguising it as a list of complaints.

“Has anyone seen Bea lately?” I ask, interrupting Zoe’s catalog of dance steps. “She has my leggings.” I’m wearing green sweatpants that I want to change; my shirt is green, too, and together they’re making me feel like Oscar the Grouch.

“Not me,” Daisy says. “She might be in the Green Room already. She’s in the first ballet.”

To get away from hearing Zoe brag about her great new part, I decide to watch the beginning of The Thorn, the first ballet, from the flies. The scaffolding of the flies forms a U above the stage; it allows the stagehands to pull the appropriate ropes and direct the spotlights from above.

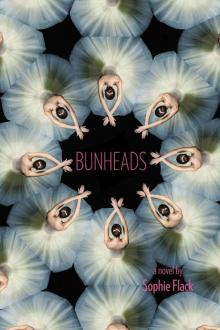

In my opinion, it’s the best seat in the house. Because it’s basically a bird’s-eye view, you can see the kaleidoscopic formations of the dancers and the way they call and respond to one another. You can see how their movements have a logic as well as beauty; it’s like a secret language of lines and angles and shapes.

Harry has a small wooden desk on the right side of the flies. A green-shaded banker’s lamp arches over his lighting charts, his scrim schedules, and whatever paperback novel he happens to be reading.

When he sees me, he looks up, and his bifocals slide down his nose.

“Hannah!” he whispers. “Let me get you a chair.”

“Oh, it’s fine, I’ll stand. I’ve got to go soon; I have to finish my makeup.”

Harry waves down to the dancers on the stage. “This piece is a total bore. Lottie gets carried around like luggage the entire time. The Bach is terrific, though.”

I look over the railing and see the way the corps, wearing pristine white tutus, move in unison as Sam drags Lottie downstage. “Yeah,” I say with a sigh.

“You okay?” he asks.

I shrug and bite my lip.

“Mattie’s been asking about you.”

“Really? Tell her I said hi.”

“She wants you to come to her performance, but I told her you’re too busy. She’s going to be an elf princess or something. Seems like every week the wife’s got to sew a new costume.”

“She’ll be so cute,” I say, watching Bea’s buoyant hops on pointe below me.

“So, how’s company life?” Harry asks.

I gaze down at my pointe shoes. “Do you want the real answer or the polite one?”

“I’m a tough guy. Do I look like I care about polite?” he responds. Teasingly, he makes a fist and flexes his forearm. It’s the size of a Christmas ham.

“Yeah, I’m not doing that great,” I say, digging my fingernail into my thigh. I should be warming up, not talking. I’m on after intermission, and I need to give myself a barre and stretch my hips.

“Didn’t get the roles you wanted.” This isn’t a question; Harry knows what’s going on.

“No.” I pull at a string on my sleeve. “It’s just so frustrating. I don’t know why I work so hard if nothing seems to happen.”

Harry exhales and pushes his glasses up on his forehead. “I don’t get it either, Hannah. I’ve seen a lot of girls come and go in this place, and there’s no question in my mind that your talents are being overlooked.”

I shake my head and kick my foot against the railing.

“What is it that you want, Hannah?” Harry asks gently.

I sigh. “I don’t know, some indication that it’s all worth it?”

I glance down over the railing at the ballet unfolding beneath us. The pizzicato pluck of the violins is joined by the drone of the cello as Sam lifts Lottie in an overhead press. The excitement builds, and the tempo picks up as the dance nears its finale.

Harry nods. “A little validation.”

“Imagine if I asked Otto for some validation,” I say. “Man, would he look at me funny!”

Harry shrugs. “My whole life people have been looking at me funny. I look funny at them right back.” And then he furrows his brow, widens his eyes, puffs out his cheeks, and pushes his ears forward.

“Oh my God!” I exclaim, laughing. “You look like a chimpanzee.”

Harry’s face returns to normal. “Exactly.” He slaps his hand on the top of his desk. “The point is, don’t let the bastards get you dow

n. You know what you need to do.”

I glance down one more time at the ballet unfolding beneath us. It’s time for me to get ready. “Thanks, Harry,” I say. “I feel a little better.”

“Anytime, sugar,” he says. “Now go get ’em.”

21

The next day Zoe comes over to me after the run-through of Stormy Melody. She steps right in my way as I’m heading to the vending machine.

“You’ve been ignoring me ever since casting was posted,” she says. Her green eyes stare right into mine, and her nose is just inches away.

I sigh and look up at the ceiling. “That’s because you’ve been insufferable,” I tell her. I try to get past her, but she reaches for my arm and gives it a little squeeze.

“I know, and I’m sorry,” she says. “I really am.”

For once she sounds like she actually means her apology. “Really?” I say. I still have my doubts.

Her brow furrows prettily, and she makes a pouty face. “I’ve just had a lot going on lately. I can tell you’re upset with me.”

“It’s actually not about you, believe it or not,” I tell her.

“Oh, Han,” she says. “I know I can be a total ass. But you mean so much to me. We’re still friends, right?” She leans her head on my shoulder. I can smell her expensive, lily-scented shampoo.

And the truth is I do care about her. We’ve been friends for five years. We got our apprenticeships together, we bought tampons together for the first time, we had our first underage drinks together. And even if we stopped speaking tomorrow, I’ll always be grateful for the way Zoe befriended me in those first weeks at the MBA. I might have died of loneliness without her.

But she doesn’t wait for my answer. “Anyway,” she goes on, “I should be a tiny bit mad at you.” She squeezes my arm and grins.

“Oh really? What for?”

“It’s March tenth—my birthday,” Zoe says, “and you and everyone else totally forgot.”

“Oh!” I pull her to me so I can guiltily hug her; Zoe always remembers my birthday, even though it happens during our summer break. “Happy birthday!”

“Twenty years old,” Zoe says into my shoulder. “Can you believe it?”

I step back and look at her. “You don’t look a day over sixteen,” I say. “What are we doing to celebrate?”

“I don’t know. Drinks? Do you have any good ideas?”

I thought about the text I’d gotten from Jacob: Prove you’re not chained to that theater. NYU party in Wmsburg, 675 Bedford Ave.

I could go and surprise him. I just hope he won’t die from the shock. “We’ll go to Brooklyn after the performance,” I say. “There’s a party that sounds pretty cool.”

I figure there’s no use moping around. Maybe a little distraction will do me good. Of course, I can imagine Otto’s displeasure if he found out that two of his dancers were planning such a field trip. But at this particular moment, I don’t feel that I owe him anything.

A strung-out-looking teenager asks us for spare change as we climb the gum-covered stairs from the L train platform. I cling to Zoe with one arm; the other I shove into the pocket of my leopard coat to keep warm as we teeter along the cracked pavement in our heels. Zoe is close to six feet tall in her Manolos, and she giggles as she stumbles and rolls over her ankle.

“Oh my God, be careful,” I cry, picturing a torn Achilles or a shattered metatarsal.

“I’m fine,” Zoe says. “In fact, I’m great!”

“You’re drunk is what you are,” I say.

Zoe holds up her thumb and forefinger half an inch apart. “Just a little tiny bit,” she says, purposely slurring her words. (She drank most of a bottle of wine at my apartment.)

As we approach the address Jacob gave me, I can feel the sidewalk vibrating from the bass.

“This is going to be good,” Zoe howls at a streetlight.

The building looks like an old factory—a place where tires or refrigerators were once made. A large garage door opens and slides along the ceiling, and a woman ducks out to greet us. She’s got a cup of some fluorescent green cocktail in her hand. “Hey, guys! Grab some paint,” she yells over the music.

Zoe and I look at each other in confusion. “Did she say grab some paint?” I ask. “And who is that, anyway?”

Zoe shrugs as we enter. The room looks sort of like an old loading dock, with a cement floor and dingy cinder-block walls covered with graffiti. Inside, the music is even more deafening.

I stop a guy passing by with a foamy beer. “Hey, have you seen Jacob Cohen?”

“Who?” he yells back.

“Jacob Cohen!”

“Ah, I don’t know. But look, we got Girl Talk,” he yells. “Right over there!” He points to a slightly scruffy but good-looking guy who’s sporting a faded T-shirt and designer jeans and spinning records on a mounted plywood bridge overlooking the party.

I scan the space for Jacob. Posters for old rock shows hang on the walls, and empty bottles of beer litter the floor. The bathroom—for which there’s already a huge line—is partitioned off by a sheet and a large piece of plywood. There’s a couple making out near a recycling bin, and a guy in a Nirvana T-shirt blowing smoke rings up to the ceiling.

“Where do I put my coat? Doesn’t this place have a housekeeper?” Zoe yells to me. Then she nudges me in the ribs to make sure I know she’s joking.

We walk toward the center of the loft, where there’s a pulsating mob of people dancing. They look strange and otherworldly, and for a second I can’t figure out why.

“What are they wearing?” Zoe screams in my ear.

I look more closely and realize that they’re covered in fluorescent paint. They’re holding buckets and cups of it, and they’re pouring it all over one another. Paint drips down their arms, turning them brilliant yellow and lime green. I see one girl wearing nothing but her underwear and splashes of chartreuse paint.

“What the hell?” Zoe hollers.

“I guess it’s creative expression,” I yell. “Like, if Jackson Pollock did a lot of acid and then had, like, a birthday party in a fix-it shop…”

Zoe points to the drinks table, which is stocked with giant plastic bottles of vodka and gin. “That’s all fine and good,” she says, “but where’s the Ketel One?”

“Try not to be a snob, just for a little bit,” I cry. I pour us drinks of slightly flat club soda and cheap vodka. “Look, they have lemons for garnish, at least.”

We toss our coats onto a pile in the corner and clutch our vodka sodas. They don’t taste very good, so I drink mine quickly. A little voice in my head warns me that I’m going to pay for this tomorrow, but I don’t care.

“No way am I going in there,” Zoe yells, pointing at the seething mass of paint-splattered dancers. “My dress is from Barneys.”

As Girl Talk mixes Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)” with the Brazilian Girls’ “Don’t Stop,” the crowd whoops and jumps in a rhythmic, pulsing cluster. The music is so loud I swear I can feel it in my bones, and almost involuntarily I start to bounce a little to the beat. The funny thing is that I’m embarrassed to dance in a situation like this; I don’t know how to do it like a normal person. I’m used to having everything choreographed for me, not all improvisational and loose. Some dancers I know are really good at party-dancing, but I fall at the self-conscious and awkward end of things.

Zoe still looks haughty and slightly on edge, and she shakes her head as I tug on her hand. I pause for a second, and then grab a bottle of bright pink paint and squirt out streams over the dancers. They rub it all over one another with their open palms, and the paint oozes through their fingers and drips down their arms.

As I watch them writhe and leap, it occurs to me that I have the entire East River between myself and the Manhattan Ballet. The feeling is thrilling.

For a moment I think of all my classmates back in Weston, Massachusetts, kids who spent the last four years going to parties and hooking up and laughing while

I was sweating and rehearsing and dedicating myself, body and soul, to dance. I don’t suppose I can really make up for lost time tonight, but I can at least join in the fun.

I kick off my ankle boots and squeeze my way into the center of the mob. The closer I get to the center, the more paint I accumulate: orange, green, blue, violet. My James jeans will never be the same, and thank goodness I’m only wearing a wifebeater for a shirt. I have streaks on my arms, splotches on my stomach—I look like a rainbow on drugs. I beckon to Zoe, who shakes her head as she nurses her vodka against the wall. No way, she mouths.

“Oh, relax,” I yell. “It’s your birthday!” Then I run over and take her by the hand and pull her toward the mob of painted dancers. I grin slyly. “It’s not like you can’t afford another dress like that!”

“Oh, fine, you win!” she yells, smiling back. She grabs a bottle of yellow paint and squirts it onto my chest. I respond by pouring a cup of hot pink onto her. And we dance wildly, crazily, covered in paint. There’s nothing graceful about the way we move at all. People step on my feet and crash into me; a girl stumbles and falls into a puddle of green. I’m not counting the beats or worrying about what steps come next—I’m just flinging myself into the dance. My heart pounds, and my rib cage rattles from the bass.

From out of the crowd, a striking, dark-skinned guy with dreads almost down to his waist materializes. Wearing only boxers and a paint-splattered gray T-shirt, he bounces over to Zoe. He touches her arm, and she whirls around.

“Oh, hi! Where did you come from?” she yells, looking longingly at his muscular chest. He responds by pulling her to him.

“Um, excuse me?” I tap him on his enormous shoulder. I don’t want to shout at him, but there’s no other way to be heard. “Hi, uh, do you know Jacob Cohen?”

Dreadlocks Guy nods. “Yeah, you missed him,” he says, voice booming. “He ducked out, like, twenty minutes ago.” Then he turns back to Zoe, who has an expression on her face like she’s just opened a truly fantastic present.

Bunheads

Bunheads